Same as probably many photographers, I get a lot of questions about my photos. And a lot of times it’s all about: What ISO did you use? What aperture? What exposure time? .. and so on. But does knowing this really help you?

I remember, that when I started taking photos, I also looked at EXIF data quite often. That’s why I actually also started adding them to every of my blog posts (not that I really see a need for it anymore :)). It was sometimes interesting to see what other people use, but I don’t remember it being so useful. And once one gets to the point that one understands what everything effects, what change of aperture does, what ISO does, and all the other, all this data looses any importance it once had. Of course as with everything, there are few exceptions, but we will take a look at those.

So lets take a look at the usual EXIF info you get, and some HDR specific stuff that I mention by my photos. Of course all the parameters are connected to each other, so one effect all the others. I will go through them separately, but will mention the connection from time to time. In few cases I simplify things, to keep this post to a manageable length.

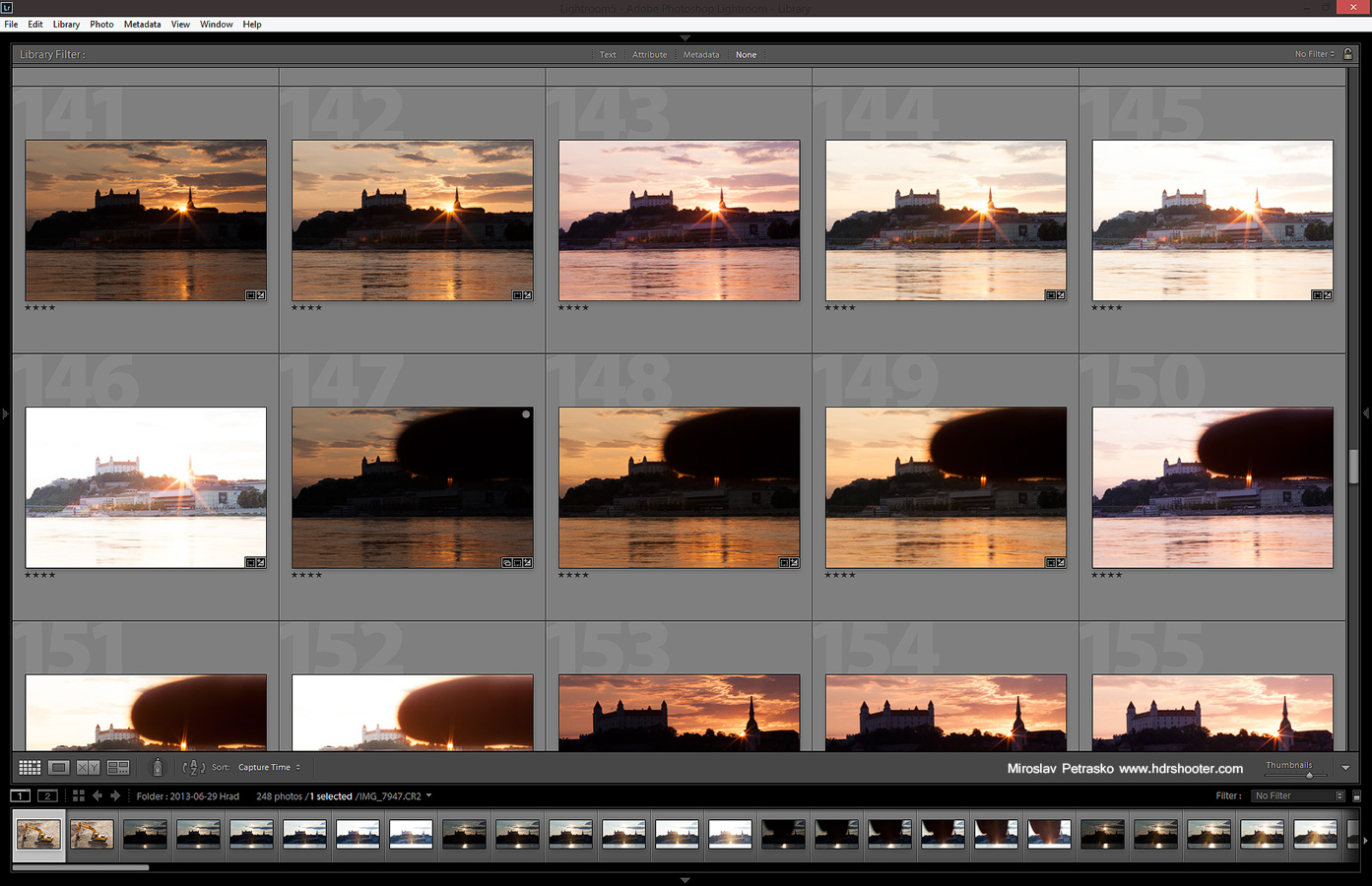

Number of brackets used

This one is really HDR specific (not really EXIF, but I include it anyway). One gets this question all the time, and the best answer is always, how many are needed. The number of brackets needed varies very greatly by a camera and the situation. After years of shooting with my camera, I came to the conclusion, that 5 exposures is enough for me 95% of the time. The only time that I take more, is when I shoot directly into the sun or a different strong light source. But even in that situation, there is a huge chance, I will not use all of them.

If one takes RAW files into account and the dynamic range they contain, I could even get most of my photos only with 3, sometimes even only 2 exposures. I just take more to be safe.

So does knowing how many exposures someone used for a particular photo help you to get a better HDR? Simply, no.

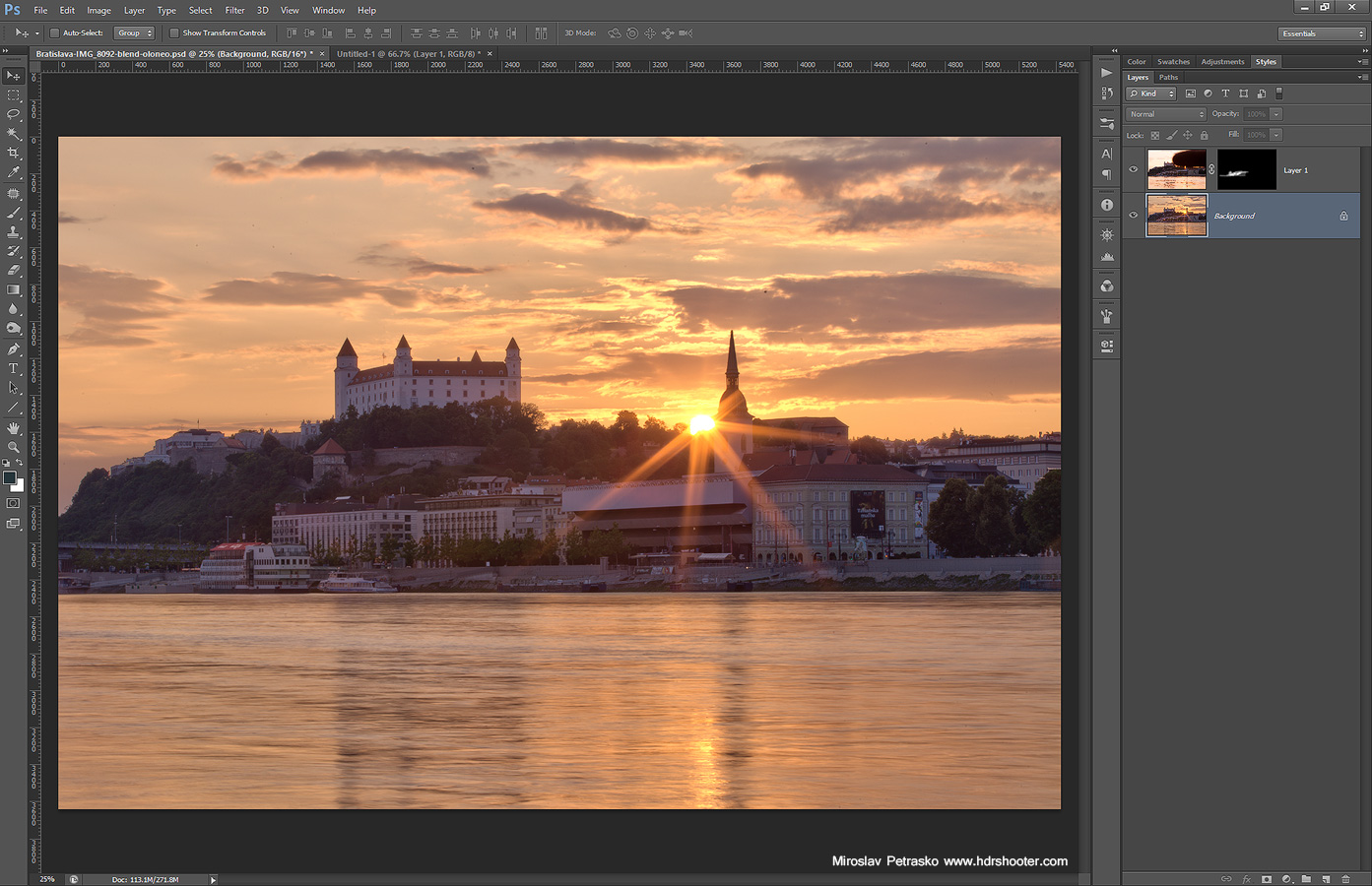

Aperture used

Knowing the Aperture can, but does not have to be useful. Aperture effect your DOF (depth of field), sharpness and light stars. Of course all of this is also affected by other parameters (lens, sensor size, focal length..) but Aperture is the main part here.

So what can you learn? Almost nothing about the DOF. As you usually don’t know the distance between the camera and the subject, the aperture on its own wont help you. With the basic rules of bigger aperture -> smaller DOF & closer to the subject -> smaller DOF covering almost all the situations, this is all you need to know.

Sharpness is very depending on the lens, and what post-processing was done. So if you see a RAW file at 100% you can judge if a certain aperture is better on that lens. Each lens has a sweet spot, and Aperture where it’s sharpest, so this can help you sometime. Still, looking at a edited photo and trying to determine this is pointless. Btw. if you leave something out of focus in your photo, make everything else look much more sharper :)

The last light stars, the effect when a light source creates a star in your photo, is very depended on the Aperture. But it’s also very dependent on the light source and the distance to that source. Again the simple rule smaller aperture -> more visible light stars is enough for one to know.

So does knowing what aperture was used help you? Usually not.

Exposure time

This is one that can be interesting. Especially in very short and very long exposure photography. Think about it this way, the difference between a 1s photo and a 2s photo is usually negligible. But the difference between 1s a 100s photo is already quite different. There are also few kinds of photography where you have to be very careful about the exposure time. For instance star photography. You have to limit the exposure time to avoid star trails (of course taking into account aperture and focal length). Also times you need to get nice light streaks from cars, or completely blurred people could be interesting. On the other side, the very short exposure are interesting when you goal is a complete freeze of motion in a subject. A good example is flowing water or waterfalls, or maybe fireworks.

So does knowing the exposure time can be useful to you? Sometime.

ISO used

As one usually changes the ISO only when it’s really needed, especially when a shorter exposure is needed, knowing what ISO was used is almost always really useless. The only time that I can think of that this would be an interesting thing, is when you want to buy a new camera and want to know the performance. But even in these case, if you don’t see the RAW file at 100%, you can’t get a good image of the performance.

So does knowing the ISO help you? I don’t think so.

Focal length

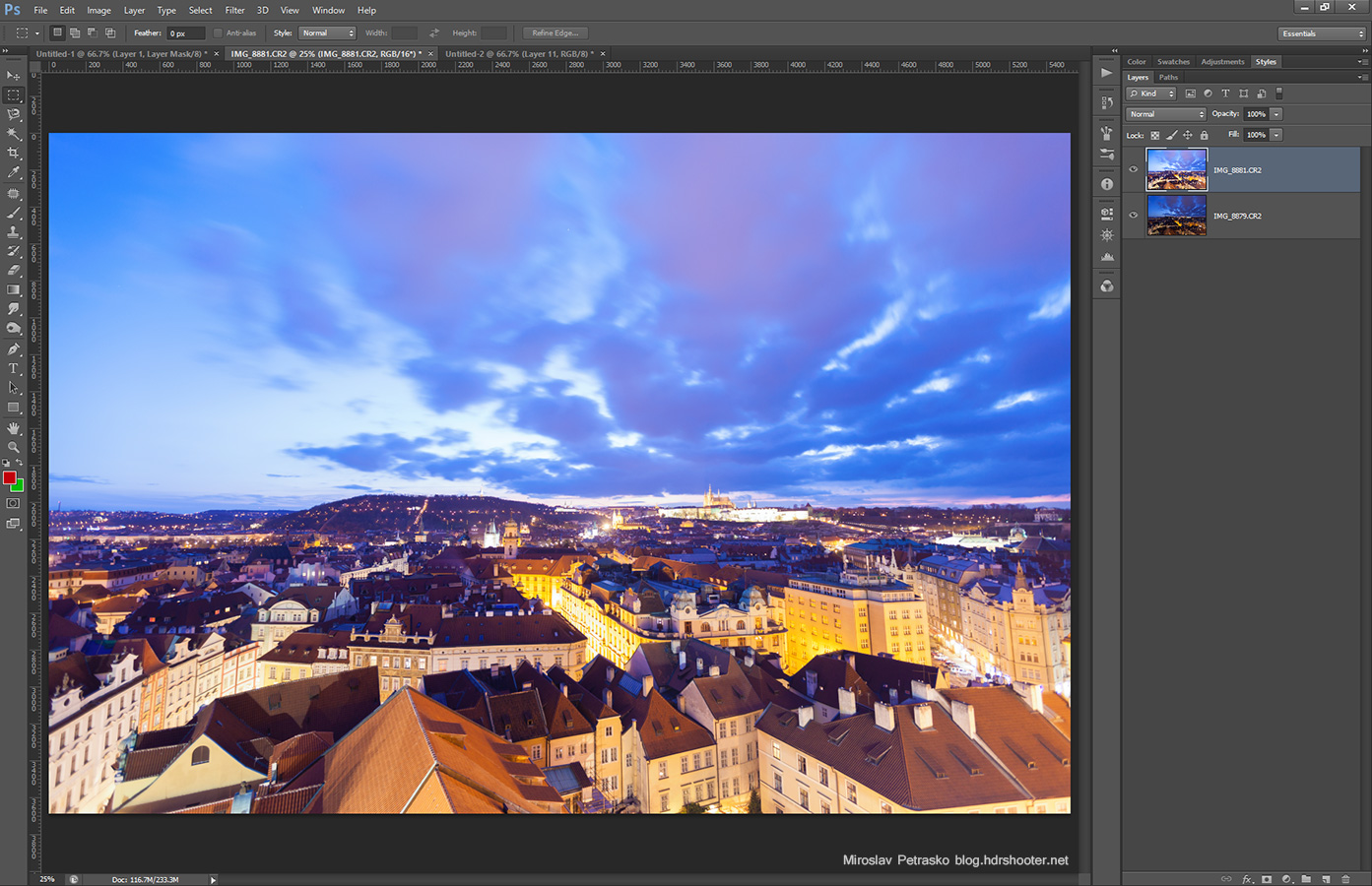

In my opinion this is the most interesting attribute you can find in a EXIF. The look of the photo, especially the perspective compression is very dependent. I you are searching for photo locations, knowing what focal length is being used can help you a lot with your preparations. Of course small differences are not important, but knowing if its wide-angle shot or zoomed in can give one a lot of help. With practice one can guess the focal length from the photo, but having a number there is easier.

So does knowing the focal length help you? I think it can.

So can one learn?

Not really. It can be interesting sometime, but not really that helpful. Much better approach is to learn what these parameters change in a photo and experiment with them. Just leaving the Auto and the P modes behind and switching to Av or M will help you more with understanding the photos than looking at all the EXIF on this blog :)